When I’m Dead, Will I Go on Desiring?

Galápagos is not for the squeamish, but then neither is living in a human body. Colombian writer Fátima Vélez’s debut novel, translated by Hannah Kauders, uses the physical realities of AIDS-related illness to ground (and question) its existential themes. It’s a postmodern plague novel, replete with pus.

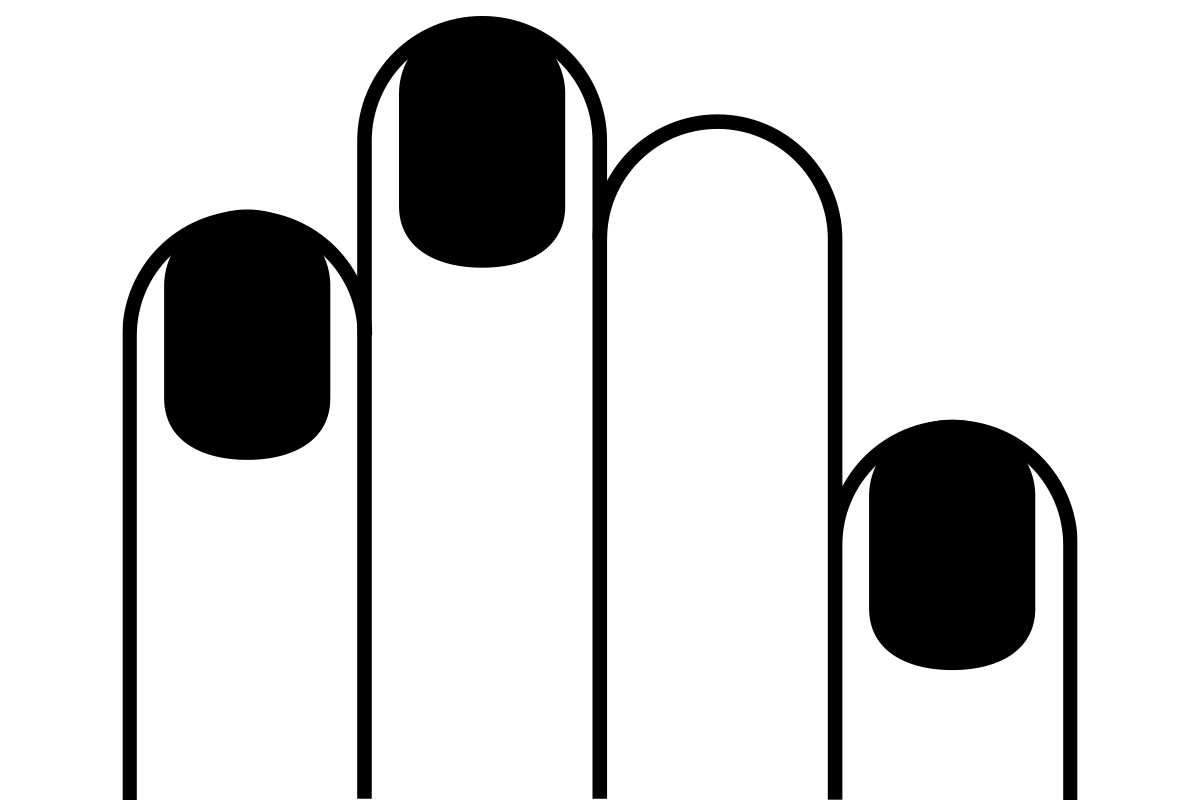

The narrator Lorenzo is a “painter who doesn’t paint.” He describes himself as not particularly hardworking; he’d rather spend the day in bed watching Jeanne Moreau movies. His wealthy boyfriend Juan B doesn’t do much either, but Lorenzo concedes that no one cares: “he’s a millionaire, and heirs are entitled to do absolute diddly-squat.” Lorenzo’s symptoms have just begun—a simple case of paronychia evolves into a “torrent of pus” threatening to dislodge his pinky nail. Before long, it’s “loose like a baby tooth,” and one nail after another falls off, leaving him with a set of bandaged nailless fingers. The horror wrests him out of his inertia and he heads to the airport:

I trust the impulse, the impulse, my only truth, and Juan B’s lack of compassion, and leave for Paris, just like that, barely any luggage, I don’t even bring my nails,

Galápagos

By Fátima Vélez, translated from the Spanish by Hannah Kauders

Astra House, 208 pp

The first part of the novel runs on like this—thought after thought, separated by commas, without any periods. Many sentenceless novels feel oppressive (whether intentionally or not), but Lorenzo’s comma breath marks are captivating. Words and ideas cascade, overlap, play tag, and eventually circle back to finish one another off. On the plane, he ruminates without interruption, and even briefly recalls a scene where the author herself appears: he had been sitting on a Paris bench after being cast out by a lover when “that bum dressed in red who said her name was Louise and then Fátima” gave him a little whiskey:

she told the tale of a group of friends who were not yet dead and no longer living but dead-alive-dead, and how they sailed through the Galápagos telling each other stories, Like in The Decameron, I said, Yes, she said, but on a fishing rig,

This premonition is swiftly forgotten when Lorenzo arrives in Paris, straight into the arms of his ex-lover Donatien, with “[his] scent of rosemary and his reddest hair.” There, he alternates between worry and denial about his new state of decomposition, as well as a more ordinary sadness. We see him fall in love with a kind of pastoral idyll beyond illness and exclusion when he visits Donatien’s grandparents in the Breton countryside:

between the chirping crickets and the tender kiss between grandson and grandmother I’m folded into a kind of happiness I’m not sure I’ve ever known, a sudden urge to work the land, an urge, a strong urge, to forget myself, my bandages, my nails, my body, and at the same time to feel it all,

But the possibility for connection is tainted—it belongs to a world of those neither sick nor queer. He yearns for the acceptance of Donatien’s straight friends, who he thinks might give him a chance, but “only if I can prove Donatien and I are together in the same way that the two of them are together, in that particular way they probably think two people should be together, the sort of togetherness required to build a home.” We get a sense of something darker brewing, which goes far beyond Lorenzo’s lethargy and nailless fingers. When Donatien says “It’s not easy, Lorenzo, they’re killing us, lots of us,” we know he’s not just talking about hate crimes. Furthermore, everyone’s been having the same dream of what Lorenzo christens the “pus man”:

when he goes to kiss you he suddenly doesn’t have lips anymore, he morphs into a white creature, it’s like he’s made of matter, the kind that spurts out when you pop a pimple, and then he engulfs you and it’s almost pleasurable, but then he spits you out, your skin starts falling off, and your teeth, and your nails, your ears, everything down to your glans,

Originally published in Spanish in 2021, Vélez’s interpretation of the AIDS epidemic emerged under the shadow of COVID-19—in a state of uncertainty. In Illness as Metaphor, and the subsequent essay AIDS and Its Metaphors, Susan Sontag argued that poorly understood diseases are loaded with corrosive, moralizing metaphors (e.g., tuberculosis as a disease of the romantics, cancer as a disease of the repressed), diverting attention from the material reality of the body. This moralizing does little to encourage a person to seek medical care. Friends urge Lorenzo to promise he’ll get tested, to which he responds, “Tested for what?” Lorenzo’s infection is no allegory for social decay or moral failure, nor is it presented with dispassionate realism; it is a physical process, a biological fact. The body in Galápagos is messy and productive:

why does paint not grow from the canvas in the same way this grows inside my body, if only I could paint the same way these stains grow on my bandages, curdling, ulcers, matter, if only I could let free that which wants to grow, why not let loose whatever is happening,

Here, I should pause to say something about the work of the translator Hannah Kauders, who’s created a surrealist language that feels undeniably real: “A pause, we’re immersed in the sky, respecting the waning light, not wanting to disturb her, let the light finish going about her business.” She’s kept all the astonishing beauty and ordinary grossness operating on the same plane, and her sense of humor appears well-matched with Vélez’s. Our bodies may be decomposing, but the text is certainly alive and well—a nod to Lorenzo’s wish, that the energy of a spreading disease might be “let loose” and redirected to produce art.

Back in the world of the novel, the news starts arriving in Paris about Colombia’s dead. And just as it seems it’s over for Lorenzo, too, he’s invited aboard The Bumfuck, a ship financed by his rich (dead) boyfriend Juan B, along with his hippy friend Paz María and a handful of other artist-types who took up the offer to cruise the Galápagos archipelago. Things take a turn toward the surreal; those aboard wear the skins of sacrificed lovers and refrigerate them at night to delay decomposition. There’s a record player imported from Germany, unlimited cigarettes, drawing paper, and a biography of Orson Welles that “must have belonged to the previous occupants.” Is this limbo? Or is the ship’s captain a modern-day psychopomp, tasked with ferrying souls across the Eastern Pacific in place of the river Styx? Narration shifts to the collective “We”; there is no “I” in a group of half-dead bohemians wearing the skins of old lovers, drinking and feasting and flirting and exchanging stories, on a ship “tailor-made” to their desires:

We can’t forget yet shouldn’t repeat them too often: to enjoy ourselves and our youth, and no no no to apathy, the creeping sense that something’s missing,

When Sontag wrote AIDS and Its Metaphors in 1989, the condition had not yet been mythologized into our narrow and nostalgic associations: New York, the queer cultural milieu, white male artists with careers cut tragically short. This vision of AIDS obscures not just the physical reality of those affected by, but also the present experience of people living with HIV. In 2013, artists Vincent Chevalier and Ian Bradley-Perrin showcased a work called Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me to illustrate the point. AIDS cannot be distilled into a single, narrow interpretation; it’s not a signifier of a moment in time or of a particular milieu. It’s not even a singular disease—it’s a condition that opens the door to a wide variety of opportunistic infections. In an interview at the 2022 Bogota International Book Fair, Vélez spoke about her starting point for the novel. She’d recently watched a documentary about the German-born Colombian artist Lorenzo Jaramillo. He was “dying in front of the camera,” Vélez tells us, when the director asked him about how he wants his story told. She recounted his response:

“I don’t want you to tell what I did or didn’t do in my life, how I painted these pictures, if they’re beautiful or not, I want you to tell what’s happening to me now, that I’m dying.”

The terms “AIDS,” “HIV,” and “virus” never appear in the novel. We rely on the context (our narrator’s queerness and the years 1989–1992) and possibly the dust jacket, which announces in no uncertain terms that the passengers aboard The Bumfuck are “dying of AIDS.” The narrative power doesn’t come from what AIDS means, but from how the afflicted community reacts to a phenomenon that defies meaning. By focusing on the personal chaos of coping with an ailing body, Vélez honors Sontag’s demand: she presents the sickness first and foremost as a naked material reality, with moral and metaphorical weight accruing only secondarily.

Any attempts the reader makes to approach the book conceptually, through philosophical or existential questions—why live/die/create/etc.?—are also thwarted by Vélez’s utterly delirious prose. The author published several poetry collections before her first novel, which is evident in her commitment to language for all the senses; every phrase has a texture, a taste, a scent, and a melody. Vélez draws from far more than just The Decameron, mining a catalogue of both seafaring and disease narratives for rich synesthetic details. Paz María, the sole woman aboard, dies after she “couldn’t stop dancing, she St Vitus danced straight into the Samana,” which refers to the jerky movements in the final stages of Sydenham’s chorea, a disorder that itself stems from a simple Streptococcus infection.

Juan B, for all his extraordinary wealth, falls sick in Colombia with what Sontag’s contemporaries might call a “scourge of the tristes tropiques” and commands a ship to the isles that supposedly inspired the theory of evolution. Surely Vélez is winking at us from below deck, setting her story at the cradle of modern biology:

A beach called La Galapaguera. A not insignificant number of giant tortoises. Pedro Vista says we shouldn’t get too close, there’s no telling how prehistory might react,

It’s also worth noting that, in Kurt Vonnegut’s 1985 book Galápagos, the post-apocalyptic human descendants on the islands have flipper-like hands and embryonic fingers described as “nubbins”—almost as if their nails have all fallen off. In the terror of a storm, Juan B even models Odysseus:

[he] begs to be struck down by a bolt of lightning, he wants to be carried off by siren song, and he cries out that he won’t let his ears be covered, and he takes the sash from his camel robe and uses it to tie himself around the waist to the creaky mast,

Looking out at a scene of giant iguanas and bathing sea lions in the calm before the storm, Paz María gets the sense that “everything has stood still from so much pleasure,” like Sontag’s idea of sex as an “an act whose ideal is an experience of pure presentness.” AIDS, she wrote, forces onto sex “a relation to the past to be ignored at one’s peril,” that evokes “the direst consequences: suicide. Or murder.” It becomes dangerous to live in the present, to find meaning in pure life itself:

Life — blood, sexual fluids — is itself the bearer of contamination. These fluids are potentially lethal. Better to abstain.

Vélez echoes this and goes further: “wrap your houses, your legs, your compassion in latex; Don’t touch, don’t look, don’t run off with strangers, and beware the gazes of others,” even as Lorenzo, waiting for the results of his blood test, is filled precisely with the “urge to make and create and hold the gaze of strangers.” The desire to create, the desire for sex, the desire for pleasure that silences the inevitable death, these are the bulwarks against existential dread; Lorenzo wonders, “when I’m dead, will I go on desiring?” though he already knows the answer.

“Galápagos is not for the squeamish, but then neither is living in a human body. Colombian writer Fátima Vélez’s debut novel, translated by Hannah Kauders, uses the physical realities of AIDS-related illness to ground (and question) its existential themes. It’s a postmodern plague novel, replete with pus.”

Finally, we couldn’t be aboard The Bumfuck without at least a nod to Moby Dick. When Lorenzo recalls that Juan B “watched me squeeze the pus from my body a hundred and fifty times each morning for god knows how many mornings,” there are echoes of Ishmael at work: “Squeeze! squeeze! squeeze! all the morning long; I squeezed that sperm till I myself almost melted into it; I squeezed that sperm till a strange sort of insanity came over me.”

Admiring the remarkable vistas of Galápagos, Paz María confronts the Janus face of existentialism. Our meaningless, futureless existence is both a great freedom and a burden:

these moments of so much present are the most dangerous of all, the strength the landscape conceals is forming a nest out there, out there unfolds all that from which we’ve fled, out there is where we realize we’re headed, straight into the jaws of disappearance, no skin of a sacrificed lover can save us

So, what’s the point? Are we not all decomposing aboard The Bumfuck as it circles the sun every 365.256 days, ailing and loving and creating, saying “no, no, no to apathy” until our eventual shipwreck? I suppose that would make it a metaphor.

Hannah Weber is a German-Canadian writer and photographer. Her criticism has been published in World Literature Today, Words Without Borders, Asymptote, and more. She lives on the south coast of England.