Ruins, Doubled

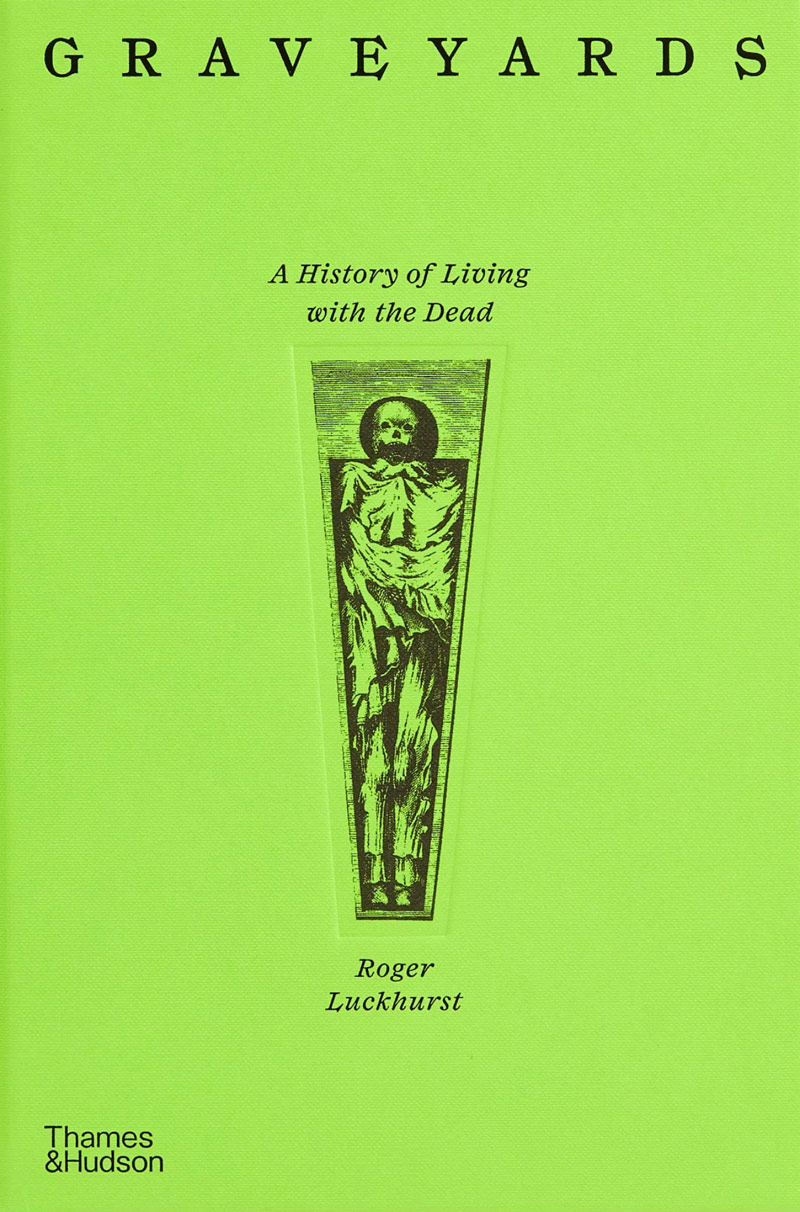

Thousands of years of recorded history offer many conflicting guides to the handling of death. Death eludes stable meaning: it is the end and the opening; the path into the unknown or toward a final form; a circle or a line; the reality upon which human history bends and rewrites itself. We have no idea what to make of death, and, as Roger Luckhurst’s sweeping, illustrated Graveyards: A History of Living makes clear, we have many ideas.

GRAVEYARDS: A History of Living with the Dead

by Roger Luckhurst

Princeton University Press, 256pp

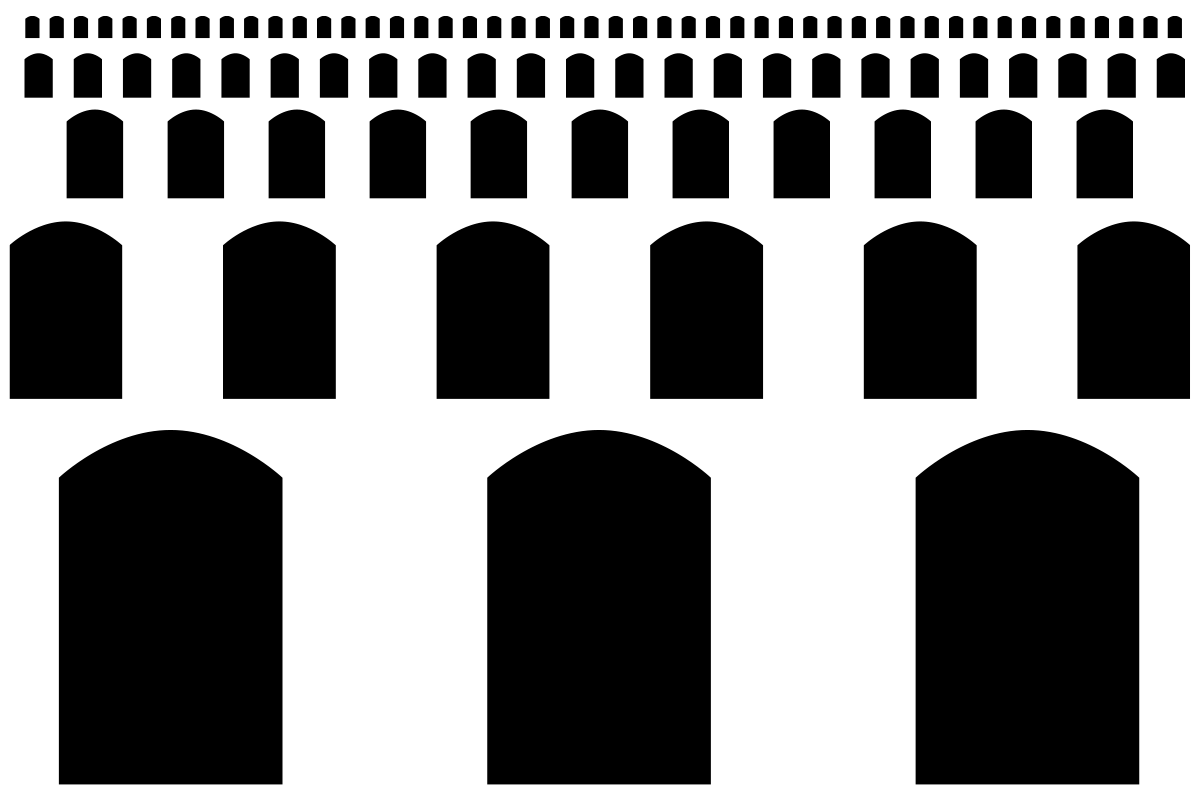

The book begins with Homo sapiens and closes with practices which are only just emerging, covering tens of thousands of years of our history. Booklist notes the title’s interest for those who appreciate “the occult and macabre,” Approaching death from this particular angle tends to separate general readers from those who kept bird skeletons as kids and already know the story of Percy Shelley’s calcified heart, which was enrobed in silk in Mary Shelley’s desk until her own death. Luckhurst argues for the book’s broader relevance, insisting that graveyards often function as “ruins, doubled” in that they may hold the traces not only of individuals but of entire cultures—and, as such, should have interest for more than the thanatophile.

The first third of the book has the ambitious aim of organizing the earliest archaeological traces of cemeteries, up to the necropolises of Imperial Rome. It’s challenging to make sense of our ancestors’ treatment of remains before a record of written language emerged. While attending to evidence of cremation and mummification, Luckhursts’s cause-and-effect analysis of theory gently establishes a historical continuum without sacrificing the authorly impulse to wax poetic or include a gnomic utterance here or there: “Perhaps death itself must always remain a rupture from the absolute outside.” Although it may seem obvious to work through this unruly mass of material somewhat linearly, a billowing, ancient, emotional tether is formed in these early sections. Perhaps it’s a sense of empathy, entwining us with our own desperation to preserve ourselves and those we love.

Jade Burial Suit, 202 BCE–9CE, courtesy Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Then, just as we’ve skirted the hinterland of prehistorical knowledge, the Last Glacial Period ends and communities turn toward agriculture and animal domestication. People lay claim to the land upon which they walk, and thus arrives the accumulation of the dead and the establishment of the necropolis. Perhaps in our times, where the cost of funeral services is generally considered to be extortionate, it is heartening to know that the fees for “professional weepers at the graveside” were begrudgingly documented as far back as the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112–2002BCE) in The Death of Ur-Nammu. “Funeral clubs” are but one example of how families would band together offset costs and prepare for the inevitability of death, taken here from Ancient Rome. Writes Luckhurst: “Every culture everywhere, from the beginning of time, complains about the cost of putting on a funeral.”

In fact, the division of labor and systems of inequality that underlie the handling of corpses and treatment of funereal observation is a through-line in Graveyards, and is one of the book’s strengths. Over and again, Luckhurst underscores the abjectness of individuals who handle post-mortem proceedings, the vast intergenerational web of hands who move the deceased into their graves. I think about how we must have lost the accounts of these workers to time. Along the Appian Way, grand structures were built next to modest accommodations for the eternal poor, but there is little evidence of those who made them.

“Death & Faith,” the second section of the book, covers a global range of cultural and religious burial places and practices and considers them within the context of tourism and anthropology: Huron-Wendat Ossuaries, Brady Street Jewish Cemeteries, Amir Timur Tomb Complex, Varanasi, Hindu cremation, Drigung Monastery, and Dhamek Stupa, among many more. Luckhurst addresses the rise of “dark tourism”—that is, tourism to sites of tragedy and bereavement—which have become yet another expression of Orientalism, with Westerners flocking to burial sites in Asia with little understanding of their actual cultural significance. Some of his observations, including his tracing of the mummy from Hollywood’s Universal Monsters films back to “mummy’s revenge” stories which only emerged after the 1882 British occupation of Egypt, will be familiar territory for grave-heads, but serve to illustrate how different ideas of death have been willfully misunderstood, or even misappropriated.

La Mort Saint-Innocent, 1520-1530.

Readers will not be surprised, however, to note the frequency with which the British Museum’s crimes are documented in this publication, and the degree to which objects can be neutered via colonialism and ensuing displacement, à la Statues Also Die (1953). But it’s not all fusty Victoriana: debate over the exchange and display of human remains has been ignited only a stones’ throw from where I live in Brooklyn, at The Bone Museum, operated by JonsBones, whose own practices as a bone trader have been a point of controversy for years. The Museum contains an unseemly “spine wall” that, for all its educational veneer, seems to exist mostly to showcase the array of human remains that JonsBones owns (and continues to sell). The provenance of these bones, like that of many that came before it, is questioned online.

“Death eludes stable meaning: it is the end and the opening; the path into the unknown or toward a final form; a circle or a line; the reality upon which human history bends and rewrites itself.”

Beyond the litany of individual manifestations of grief and remembrance, Luckhurst reminds us of “the brute fact that the dead far outnumber the living.” Thus, the third section of Graveyards concerns “The Numberless Dead” and the problem of our sheer accumulation of people who have passed, who we aim to remember through labor and politics and art. Luckhurst discusses the post-industrial cemetery reform that led to the founding of garden cemeteries (like Greenwood in Brooklyn); the tombs of rulers like Qin Shi Huang (the first emperor of unified China) or Vladimir Lenin; the memorialization of those lost during war and genocide, including the ongoing genocide being committed by Israel and the United States, and the bombing and bulldozing of at least six Palestinian graveyards by the IDF at the time of the book’s writing. Luckhurst probes newer, futuristic forms of post-mortem proceedings like Silicon Valley’s obsession with cryogenics, and takes a brief look into the cult of Santa Muerte, one of the fastest growing religions in the twenty-first century.

Hugo Simberg, The Garden of Death, 1896.

I did have a bone to pick, if you will, with Luckhurst in his framing of “natural burials,” which are the internment of bodies with only biodegradable materials. He presents this practice as the offspring of “Romantic and Transcendental ideas about natural sublimity of landscape.” While the author makes it clear that the improper storage of bodies can have unsavory results (such as the bursting Holy Innocents Cemetery incident or the twelve thousand corpses stored under Enon Chapel), his evaluation of natural burials falls short. Metal caskets and many embalming fluids are unsustainably produced, creating an ecological urgency on a rapidly heating planet. For many who choose natural burials, there is an environmental dimension alongside spiritual and logistical concerns that Luckhurst fails to properly acknowledge.

But this is only a minor quandary of mine in an otherwise indispensable book. Illustrations throughout guide the reader like Dante’s Virgil to interpret aesthetic-spiritual sensibilities across religion and time: the overwrought symbolism of neoclassicism jumps off the page next to the impermanence of life as portrayed in Japanese Buddhist art via the nine stages of bodily decay. Princeton University Press’s gorgeous production, designed by Tom Etherington, includes a textured, vermilion paper-over-board cover with blind stamping on the front of the book inlaid with an eighteenth-century Richard Gough illustration. Patterned endpapers complement an evergreen ribbon and H&T bands that match the cover stock. The color palette skirts the doom and gloom of books of similar subject matter, and gestures instead at the vivacity upheld by the existence of graveyards and rites of passage to death.

Graveyards’ pages are full of realities both bleak and liberating. As technologists breathlessly predict that AI could lead to superhumans, augmented by machines, death in all its timeless authority, remains. Near the end of his book, Luckhurst asks: “Might technology, if it cannot end death, alleviate the rawness of grief and traumatic loss?” Perhaps his question is rhetorical. I doubt he had a wry smile when he wrote it. Or perhaps he understands that without even giving an answer, you and I both know.

Naomi Falk is a writer, publisher, and chainmaille artisan. She is the founder of Crop Circle Press, where she co-produces volumes of visual art and experimental literature. Her first book, The Surrender of Man, was published in 2025 by Inside the Castle.