Vegetal Mysticism

Outwardly, there need be nothing noticeable about a mystical state. It’s our perception that changes—our way of seeing the world. In this state, we begin noticing in a different way, and things that ordinarily fade into the background suddenly arrest the attention. Like grass. Take the story about the seventeenth-century mystic Jacob Boehme. While sitting in his room one day, Boehme fell into an ecstatic state, just like that. Perhaps fearing for his sanity, Boehme decided to test the reality of the ecstasy with the oldest trick in the book: leaving the house and taking a walk in the green fields outside his house. But the ecstatic state continued unabated. It now seemed to him that he was staring into the very being of plants and grasses and that vegetal life harmonized with his transformed perception. Touching grass, the mystic was himself touched by grass.

Mystical descriptions of plants have become platitudes. It’s easy to quote William Blake seeing “heaven in a wild flower” without thinking of the weirdness implied. Why plants? Mysticism is about scaling the heights of human consciousness; it’s about “peak experiences.” Plants grow on the ground and appear to have very little to do with ecstatic, out-of-this-world experiences. Aldous Huxley foregrounds this paradox in his hands-on foray into mysticism, The Doors of Perception. After swallowing a pill of mescaline, Huxley finds himself entranced by a vase of flowers. Huxley reflects on how different his perception of the flowers was after entering an altered state. Before taking mescaline, the flowers were nothing more than an arrangement of colors; after taking mescaline, Huxley writes, “I was seeing what Adam had seen on the morning of his creation—the miracle, moment by moment, of naked existence.”

I am interested in mysticism as a power of noticing, of radical sensitivity, that shapes our sense of the world. The mysticism I’ve encountered is so intense in its emphasis on surrender that it can disrupt the boundaries of the self entirely, both in the sense of an individual “me” and in the sense of a collective species “we.” The practice of contemplation promises to elevate humans beyond our current understanding of the mind while also plunging them into an abyss in which the mind does not yet exist, or rather, exists in a form at odds with ordinary awareness. The traditions from which I learnt to practice contemplation are about letting the human mind become something besides what it ordinarily is, by learning how to recognize and eventually experience kinship with other-than-human minds.

In my approach to mysticism, the status of the human is held continually in doubt. For almost a decade now, I’ve been learning how to enter contemplative states, and I’ve been drawn to mystical texts that challenge the elevation of human animals above other creatures. “Men would condemn such a [mystical] state, saying it makes us something less than the meanest insect,” wrote the seventeenth-century French mystic Jeanne Guyon in Spiritual Torrents, a manual that shows just how decentered the human may become in mysticism.

Over the past years, I’ve been gathering examples of mystical texts that have affirmed in ecstasy an experience of powerlessness that seems almost vegetal in the role it gives to passivity. What I call vegetal mysticism emerged from my experience of contemplation but also of a state in which I seemed to become “lesser than the meanest insect,” to quote Guyon again, the passivity of which I find to be more effortlessness than inertia. But the vegetal is not actually passive, nor is mystic surrender truly an abandonment of effort. In mysticism—as in vegetal life—activity is everywhere apparent, but in a way that typically escapes human notice.

Let’s start at the very start. Life exists by virtue of passive syntheses that continually contract matter into new forms, by virtue of an effort that is imperceptible yet ineluctable. In other words, words you might find on a greeting card or a bumper sticker, life finds a way. As Gilles Deleuze once wrote, those passive syntheses are contemplation, and humans are not alone in making contemplative acts: “by its existence alone, the lily of the field sings the glory of the heavens, the goddesses and gods – in other words, the elements that it contemplates in contracting.”

The persistence of this passivity helped me to connect to plants in new ways. Although I knew that some psychoactive substances are understood, both popularly and traditionally, to connect humans to vegetal allies, it was my hunch that other ways of making such connections must have existed in histories of spiritual exercise. It seemed to me that although we now have a good sense of what our minds become “on plants” (to borrow Michael Pollan’s phrase), we lack a sense for our mind as plants: a sense for how, without ingesting plants, our minds nonetheless seem to become vegetal through spiritual exercises. But how might we describe what the philosopher of vegetal life, Michael Marder, describes as practices of recognizing “the plant in us”? How might we linger on the ways in which such practices afford alternative paths to inducing mind-altering experiences?

For me, learning to recognize “the plant in us” took some time. A background studying ecology and religion had primed me for an entwinement with vegetal life, but it was spiritual exercises that changed things. Gradually, over the course of a year or so, daily practice attuned me differently to the world. I became able to slip easily into contemplation and discovered a state not just of concentration, but also of receptivity and heightened sensitivity. The experience required my being able to relax deeply, at which point I became aware of what I can only describe as a kind of light suffusing me and everything around me from above, as if I had stepped suddenly into the sun. When mystics explain what it’s like to enter the deeper stages of contemplation, they often draw such comparisons, with another early modern mystic, Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, explaining that “we must…remain attentive to the presence of God…like a plant unfolding itself to the rays of the sun.” The comparison with plant-life in mysticism is a metaphor but not for that reason a fiction; it comes of noticing what happens to consciousness during contemplation. In fact, mystical literature seems almost incapable of avoiding vegetal imagery when writing about the way in which the mind is altered during contemplation.

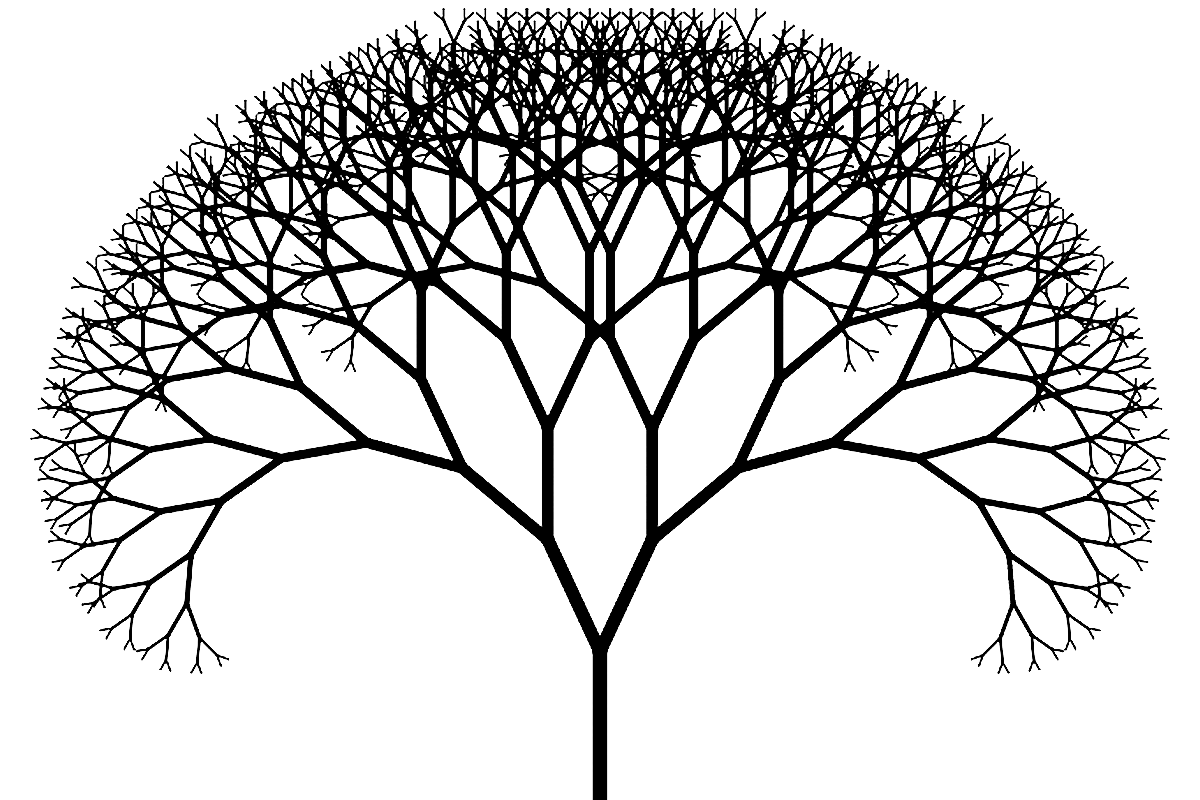

For instance, during the medieval period, the imagery of trees was so common in European mysticism that the historian Sarah Ritchey coined the term “spiritual arborescence” to describe the links between mystical and vegetal life. Trees, with their branching forms stretching upward to receive the sun, were used to illustrate the mystical ascent, and trees were also sites of spiritual revelation and contemplative practice. Some contemplatives, such as the medieval hermit Edigna of Puch, even took up residence in trees, communing with God in the way a trees’ leaves commune with the elements, in radical openness.

The entwinement between practical contemplation and vegetal life is inseparable from the nature of consciousness. Consciousness tends to be associated with brains, meaning that the discussion of consciousness is often zoocentric, focused on animals and especially humans. Yet many philosophical and scientific traditions have observed that consciousness is observable across a wide variety of species, if not all life. The molecular biologist Anthony Trewavas rejects the idea that the behavior of plants, for instance, is reducible to reflex reactions and mechanical processes. Citing Lynn Margulis and Carl Sagan, he writes: “not just animals are conscious but every organic being, every autopoietic cell is conscious. In the simplest sense, consciousness is an awareness of the outside world.”

Vegetal mysticism is awareness of the outside world; it’s the contemplation of life. A few years into my work on vegetal mysticism, research put me in the way of psychoactive substances used to induce mystical states (which in labs are known as vegetal entheogens and at music festivals as shrooms). Early one spring morning, I ingested a carefully controlled dose. Over the course of several hours, I experienced the substance’s signature “high.” I remember how everything glowed, especially the trees in the back garden, and that I was bathed in a strange light. With my mind on plants, plants revealed themselves to me. Except that the revelation was not new. I had experienced all of it in contemplation. When the trip subsided, I was surprised at how familiar it had been: I knew this feeling. The temporary mind-alteration caused by the psychoactive substance I had ingested had brought me to a state I recognized from contemplating “like a plant.”

Contemplating like a plant involves doing spiritual exercises daily, what Aldous Huxley called “the path of Martha”: a work of practice, distinct from the route offered by a psychoactive substance. For Huxley, a mind on plants (in his case, mescaline) had taken not the path of Martha but “the path of Mary,” effortlessly enjoying contemplation “at its height.” Huxley is justly famous for his embrace of entheogens and his belief in the curative powers of mescaline, but The Doors of Perception is also laced with arresting reflections on practice. “Now I knew contemplation at its height,” writes Huxley, commenting on the mescaline trip, while adding: “At its height, but not yet in its fullness.” Contemplation is a trait as well as an experience, and Huxley reflected that taking mescaline alone would not induce the “right kind of constant and unstrained alertness.” While the contemplation provided by mescaline was remarkable to Huxley it was not self-sustaining, nor did it induce “alertness” beyond the trip. And because Huxley was interested in being able to practice such “alertness,” he reasoned that he would need to walk the path of Martha after all.

Most fascinating to me are the mind-altering states that do not involve ingesting plants but instead rely on cultivating “unstrained alertness” like a plant. I am inclined to agree when psychedelics research suggests that plants—but also other vegetal life, such as fungi—can alter our minds in ways that are not fundamentally dissimilar to what happens in contemplation; my own and others’ experience seems to confirm this. But focusing on experiences generated by psychoactive substances at the expense of Huxley’s “path of Martha” provides a one-sided view of both minds and plants. Vegetal mysticism is not psychedelic-induced mystical experience; vegetal mysticism is the vegetalizing of mind through contemplation. Such mysticism is born of the realization that consciousness is already vegetal, and that what is needed in order to get high is to get low: to go deeper, until we find the plant in us.

But depth is relative. Marder, for his part, writes that

if we wish to discover vegetal mindfulness in ourselves, we should look no further than our bodies’ unconscious attention to the surroundings. Like the leaves of plants, our skin senses humidity and temperature, light gradients and vibrations. Without knowing it, we pay attention to the world on the surface, from the porous, essentially open, cutaneous remembrance that keeps our living bodies enact and, at the same time, communicate with whatever lies beyond them.

The plant in us hides at the boundaries of our physical contact with the elements. Slipping into contemplation, I find the practice is like an unfolding. Contemplation is more intense and long-lasting if I first contract my awareness, drawing it into my heart center. From there, I open outward, slowly at first and then faster, bringing my awareness to the surface of my body until I’m all sensation, all skin-tingling receptivity.

The gesture that finally brings me into contemplation is simply a continuation of this outward-unfolding, and I can never quite predict when the contemplative state will take hold. I wait, until I feel an invisible light saturating my field of mental vision. If I try to distinguish my thoughts from my sensations at this point, I find I’m not able, because the light overpowers my ordinary way of processing sense impressions. Like the leaf of a plant, I’m powerless to do anything but receive this light, but like the leaf I’m also filling up with energy. The bliss of this experience I find hard to articulate, but surely it has to do with the paradox of powerlessness mingled with power, and the vegetal notion that to create, act and make might themselves be forms of receptivity—a receptivity to power that might in time be converted into new forms of life.

The whole time I’m in the contemplative state, I don’t want to be anywhere else. But even when leaving it I find I am still within it, to a certain degree. As I move about and begin to turn more animal than vegetal, I can, if I put my mind to it, remain connected to the plant in me if I remain open and receptive. There is a knack to maintaining relaxed and passive while your body is engaged in activity. Paying attention to breathing helps. I follow my breath and as I feel the rhythm of alternating effort and release, I am reminded of contemplation. Every time my body surrenders to the air, I remember to surrender to the invisible energy that flows through me, like sunlight through a leaf.

Simone Kotva is a philosopher and theologian. She is the author of Effort and Grace: On the Spiritual Exercise of Philosophy (2020) and co-translator of Félix Ravaisson’s Fragments on Philosophy and Religion (2025). Her second book, Ecologies of Ecstasy: Mysticism, Philosophy and Vegetal Life, is forthcoming with Columbia University Press.